|

The Evolutionary Theory of

Sex:

“Paternal Effect”

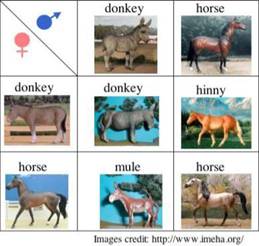

“Paternal Effect” helps explain centuries-old biological

observation that both mule and hinny look closer to their

fathers.

Some characters belong to one sex

only (primary and secondary sexual traits, many useful

characters—egg, milk, caviar production). Because phenotype

of one sex lucks the character, one can judge genotypical

sexual dimorphism by reciprocal effects. It follows that

while with “old” stable characters the genetic contribution

of father to the offspring is somewhat smaller than that of

mother due to maternal effect stipulated by cytoplasmic

inheritance and uterine development, with “new”,

evolving characters paternal contribution must exceed

the maternal one. This may result in the compensation of

maternal effect for such characters and even in the

initiation of opposite “paternal effect”. In other words,

when “new” characters are transmitted paternal characters

must to some extent dominate over the maternal ones.

Reciprocal “paternal” effect allows

distinguishing the character that undergoes evolution from

the stable one. The direction of character evolution can be

determined based on genotypical sexual dimorphism and

heterosis.

Hence considering heterosis as a sum

of new evolutionary achievements acquired through divergence

it can be suggested that paternal contribution to heterosis

must exceed the maternal one. In the light of new views, it

becomes clear why in heterosis we, as a rule, observe

increasing of the characters useful for the human, but not

for the species itself. In addition, this phenomenon is

independent of species undergoing heterosis. Heterosis gives

nothing to the species and can be even unhealthy. But since

selection can be considered as human-forced artificial

evolution for those species, the direction of this evolution

and the direction of heterosis are in accordance with

human’s interest, but not with the interest of the

particular species.

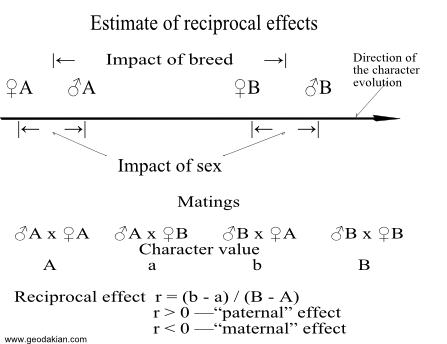

Considering evolution of the character in Phylogeny as

some kind of an abstract “movement”, one can speak about a

“distance” between male and female sex on this character.

Suppose that an initial form diversified in

Phylogeny into

two different forms (breed, line or race) by this

character. Then, according to “phylogenetic rule of sexual

dimorphism,” we can expect that males from both forms (A

and B) should be more advanced compare to females. So, one

can speak about the

“distances” between breeds according to the trait (how fare

they are gone from each other) and between males and females

within each breed (Figure). It’s possible to

distinguish the “impact of breed” and “impact of sex” in

hybridization. The effect of heterosis can tell about the

“distance” between the breeds and sexual dimorphism—about

the “distance” between the sexes. The direction (“maternal”

or “paternal” effect) and value of reciprocal effect can

tell about divergent or convergent evolution of the

trait. Therefore appears a

possibility to explain more completely the reciprocal

effects, which are nothing more

but the vector sum of maternal and paternal effects.

The following formula can be used for

measurement of reciprocal

effects (r): r = (b - a) / (B - A), where A and B

—are values of the

character for the initial forms; a —the same for

hybrid ♂A x ♀B; b —for

reciprocal hybrid ♂B x ♀A. Then positive value of r

(r > 0) will correspond to

“paternal” effect, negative (r < 0)—to

“maternal”. Absolute value of r (│r│) will provide relative measure

of the effect in units (B - A).

What characters can be classified as

the “new” ones, as those being in evolutionary process? In

humans “new”, evolutionary young characters are all social,

psychological characters related to the large hemisphere

cortex of the brain, to the brain functional asymmetry

(first of all, apparently, abstract thinking, spatial

vision, humor and other creative abilities). In agricultural

animals and plants, these are evidently all economically

valuable characters, which are selected by man artificially

and according to its goal. In animals these characters are

early maturity, productivity of meat, milk, eggs, wool etc.

Consequently, one could expect that all economically

valuable characters are connected with “paternal effect”,

i.e. the character of father's breed or line dominates over

the mother's one.

Hens:

The “paternal effect” was observed on brooding instinct,

early maturity of daughters, egg laying capacity, and live

weight

“Maternal effect” was observed on the weight of eggs.

Pigs:

The “paternal effect” was observed on the characters for

which the selection took place: the vertebra number

(selection for long body), the length of small intestine

(selection for best food utilization) and growth dynamics

(selection for early maturity).

The “maternal effect” was observed

for the weight of newborn piglets.

Cattle:

The “paternal effect” was observed on milk yield and fat

production (amount of fat).

Small “maternal effect” is observed for the percentage of

fat in the milk.

Large father's contribution to the

egg yield of daughters was explained by the fact that in

hens the female is heterogametic and the male—homogametic,

therefore its single X-chromosome the hen receives from its

father (Morley, Smith, 1954). If so, it should be expected

that in mammals everything must be vice versa, since their

males are heterogametic, i.e. greater contribution must be

observed, notwithstanding the fact, whether an “old” or

“new” character is inherited. According to new theory,

disregarding the gamete pattern of sexes, in all

cases the “paternal effect” for evolving (selected)

characters must exist.

Back

to

Sexual Dimorphism—Forms

More about

“Paternal Effect”:

Existence of the “Paternal Effect” in the Inheritance of

Evolving Characteristics.

Geodakyan V. A. Doklady Biological Sciences, 1979, v.

248, N 1-6, p. 1084–1088. Translated from Doklady Akademii

Nauk, Vol. 248, No. 1, pp. 230-234, September, 1979.

Evolutionary Logics of Sex Differentiation. Reaction Norm,

Sexual Dimorphism, "Paternal Effect".

Geodakian V. A.

|